This second article in our series examines what is meant by ‘services’ and their apparently key role in the richest capitalist states where moving away from production of commodities is regarded as essential to economic advancement. Indeed, despite the setback of the 2007/8 financial crash, World Bank figures show that ‘services’ represent a higher proportion of GDP for the world economy as a whole. For the UK 77.4% of GDP was attributed to ‘services’ in 2018.

Part Two: The Value of Capitalist Services

Introduction

In the first part of this article we noted that four out of five jobs in the UK are now officially classified as ‘services’. The UK is in the forefront of a tendency amongst the richest capitalist countries whereby ‘services’ form an increasingly large part of GDP.

Drawing from this, there is a growing consensus amongst capitalism’s economic pundits, especially of the Anglo-Saxon variety, that the service sector is now more productive than manufacturing industry. Clearly this is a very different argument from in the past when economists used to maintain that a higher rate of productivity in the manufacturing sector enabled advanced economies to sustain the burden of an expanding, less productive service sector. Yet, if the idea that services are the main source of ‘added value’ in an economy is nonsense from a Marxist perspective, for the capitalists who don’t accept that labour is the source of all value and who judge the value of everything in terms of money and price, it matters only that ‘services’ apparently generate economic growth.

Wage Labour is the Real Source of New Value

The term ‘service’ for Marx defines labour which creates a use value for someone else who is prepared to pay for it. This definition is based, not on ‘what’ is created or on the particular kind of work that is carried out, but on the relationship of the labourer to capital. The service worker may be a live-in domestic help or nanny who works for a wage, a window cleaner or a tutor engaged to give music lessons for a set fee, right through to the whole gamut of lawyers, preachers, prostitutes, and so on. In all these and similar instances the labour of the ‘service provider’ produces something of use to the purchaser who in turn pays for it directly out of their income or revenue. Nevertheless, no matter how ‘valued’ the service may be to the purchaser, in terms of society’s overall wealth they generate no new value because the recipient of the service pays for the full amount of labour expended in creating it. In the capitalist society of Marx’s day personal purchase of services was the norm but his basic insight that the labour of the service worker is paid for out of revenue or incomes holds for later advanced capitalist economies with welfare systems and state bureaucracies funded out of taxes. Marx described taxation as enforced saving and to the extent that public services — including the wages of the workforce — are paid for out of taxation (largely deducted from workers’ wages, but also from profits) they fall within his definition of ‘services’ — i.e. as providing something useful, in this case for the holding together of capitalist society as a whole, and paid for out of society’s total revenue.

From a Marxist standpoint service work is unproductive not because the work is unnecessary, brain-work rather than manual, or whatever other subjective criteria, but because no new value is created beyond the labour used up in creating the service. It is otherwise when a wage worker is engaged to produce commodities for a capitalist employer.

In this case the terms for the sale of labour power have changed and the whole relationship between the person doing the work and whoever is employing them are different. Now the employer is buying the labour power of the wage worker for a set amount of time during which their labour will be expended in producing commodities (exchange values) which have no direct use value to the employer since the only reason for producing them is that they can be sold on for a profit. Unlike the personal payment a capitalist might make for a service, the wages a company or business pays to its commodity-producing workforce come from a capital fund which will be replenished by far more than the cost of the wages themselves once the profits are realised for the commodities sold. This is possible only because the workers are obliged to work longer and produce more commodities than if they were simply reproducing commodities equivalent in value to their wages. For example, it may take a worker in a food processing factory half a day to produce commodities equivalent in value to their wages but the working week is five days. The value of the commodities produced by the worker during the remaining four and a half days is claimed as a natural right by capital which fails to recognise that it is this unpaid surplus value which is the source of capital growth.

Here then, for Marx is ‘productive labour’: labour which is employed not simply to produce a use value but which produces commodities (exchange values) and in so doing produces surplus value over and above the value of wages.

Capitalism today is even more in denial about labour being the source of value than it was in Marx’s day. For the capitalists it is capital which produces new value, although they cannot explain how this happens. It is unsurprising therefore that their definition of service work does not coincide with that of Marx and, as we shall see, includes both unproductive and value-producing labour power as well as other categories of unproductive labour, notably retail and bank workers, associated with the circulation of capital and commodities.

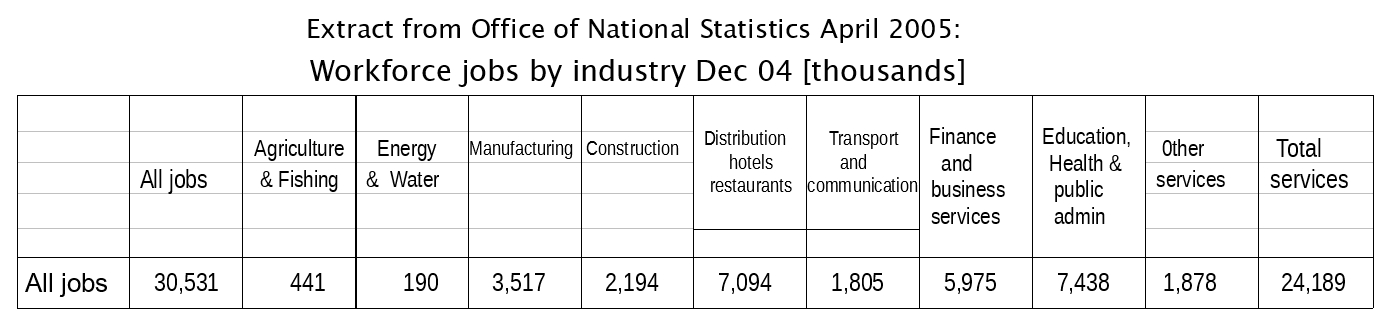

If we take this extract from an official table as a more or less up-to-date depiction of the UK workforce we can see that these categories neither coincide with Marx’s definition of services nor the marxist distinction between productive and unproductive workers. For the Office of National Statistics [ONS] five out of the nine categories of jobs are defined as ‘services’. By contrast, using Marxist criteria, if we assume the first four categories are predominantly composed of productive workers1

then, at a rough guess, we can suppose that several more million or so workers categorised by the ONS under service work should be classed as productive. Take transport, for example. Marx clearly argues that when the exchange value of commodities increases as a result of their being transported from one place to another then the labour of those who do the transporting is productive labour.

"And although in this case the real labour has left no trace behind it in the use-value, it is nevertheless realised in the exchange-value of this material product; and so it is true also of this industry as of other spheres of material production that the labour incorporates itself in the commodity, even though it has left no visible trace in the use-value of the commodity."2

It is otherwise ‘in the case of the transport of people’ which ‘takes the form only of a service rendered to them by the entrepreneur’.3 However, our point here is that a substantial part of the workforce in a category classified by the bourgeoisie under ‘services’ is engaged in productive labour, as defined by Marx’s labour theory of value.

Similarly with other categories officially classified in the ‘service sector’. We cannot assume that the word ‘service’ means unproductive labour. For instance, much of the labour subsumed under the category of ‘distribution, hotels and restaurants’ is involved in producing commodities (creating new value) or adding to their value rather than in the simple deliverance of a use-value as a personal service. There are 2.5 million hotel and restaurant workers in the UK, most of them are wage workers employed by a capitalist enterprise and are not simply receiving payment for providing a personal service. Here is Marx again:

"The cook in the hotel produces a commodity for the person who as a capitalist has bought her labour— the hotel proprietor; the consumer of the mutton chops has to pay for her labour, and this labour replaces for the hotel proprietor (apart from profit) the fund out of which he continues to pay the cook."

This is quite different from when

"I buy the labour of a cook for her to cook meat, etc., for me, not to make use of it as labour in general but to enjoy it … then her labour is unproductive … The great difference (the conceptual difference) however remains: the cook does not replace for me (the private person) the fund from which I pay her, because I buy her labour not as a value-creating element but purely for the sake of its use-value."4

The ONS table, moreover, doesn’t demarcate the number of workers in relatively new, growing sectors of the economy such as media and so-called creative industries. On the latter the Financial Times ran an article last year which provides more recent information.

"Britain’s creative sector has almost doubled in size in a decade, spurred on by rapid growth in the radio, television advertising and software industries. The creative industries account for almost 9 per cent of the economy, according to the latest figures, as modern sectors gain share at the expense of older ones such as manufacturing and farming. … In 2002 the creative sector accounted for £80.9bn of gross value added to the economy — a measure of genuine value added to the economy — according to the Office for National Statistics. The 93 per cent rise over the decade compares with an increase of only 70 per cent for the economy as a whole."5

When we consider how much of the ‘creative industry sector’ is run as a capitalist profit-making enterprise it is clear that the work of actors, artists, playwrights, etc., regarded by Marx as ‘insignificant compared with the totality of production’ nowadays does indeed add ‘genuine value’ to the economy by courtesy of a workforce which is just as much engaged in the production of commodities as any factory worker.

"It is the same with enterprises such as theatres, places of entertainment, etc. In such cases the actor’s relation to the public is that of an artist, but in relation to his employer he is a productive labourer."6

Even the BBC’s supposed dependency on licence fees is a thing of the past and the ‘public service broadcaster’ is highly involved in the competitive media business. Here is another indication that there are millions of workers within the officially designated ‘service sector’ whose labour produces commodities (and therefore new value) and who are paid out of capital (or profits).

Clearly, therefore, an examination of the official workforce statistics from a Marxist standpoint reveals that millions of jobs classified by the bourgeoisie as service work do in fact involve productive labour. The size of the value producing labour force — in Marxist terms — is possibly twice as large as the figures suggest. Instead of around 6.3 million value-creating jobs we can estimate there are at least 12 million such jobs. However, this still means around three-fifths of the 30 million or so jobs in the UK’s new economy are unproductive in value terms. Extrapolating for the employed workforce (which is smaller than the number of jobs) we can say that roughly 17 million of the 28 million employed workers do not produce new value. In terms of the population as a whole (almost 58 million) this means that for every value producing worker there are close on five other people. If UK economic wealth was in reality generated entirely by the domestic economy, then this would indeed signify both a high rate of surplus value and the generation of a high level of absolute value from sectors outside of the traditional areas of manufacturing, extractive industries and construction. Yet, even as we acknowledge the existence of commodity-producing, value-generating sectors amongst the officially-designated service workforce, it is not primarily these jobs which the likes of the Institute for Fiscal Studies claim “create higher added value for the country”.7

On the contrary, with the possible exception of the ‘support services’ sector which includes value producing workers and the ‘media’ — which sector the official statistics do not specifically categorise — it is precisely the unproductive sectors of their ill-defined ‘service sector’ which the bourgeoisie claims are amongst “Britain’s biggest wealth creators”. (Again, we are referring to surplus value, not nominal currency values.)

The Mystery of Value Added

Earlier this year the Financial Times set itself the task of “unravelling the riddle of wealth creation” and only revealed how the inability to see beyond nominal money values ensures that the real source of wealth creation will remain forever a mystery to the capitalist class. However, in its attempt to solve the mystery, the FT published the DTI’s (Department of Trade and Industry) lists of the companies and sectors it designates as the UK’s top ‘wealth creators’: that is, those which make the biggest financial profits.

What the FT shows is that five or six out of ten8 of the DTI’s most profitable sectors do indeed fall into the UK’s officially-designated service sector. A further glance tells us that banks predominate. (They comprise 5 out of the 12 top UK companies and head the ‘wealth creation’ sector list). While the profitable ‘support services’ (anything from Rentokil to Jarvis) and ‘telecoms’ sectors will include both productive and unproductive labour, the retail sector (8th on the list) is on the whole unproductive in value terms.

There are about 2.8 million retail workers in the UK. According to Marx, their jobs are part of the cost of circulating capital in its commodity form. The retail sector comes under what Marx described as ‘merchant’s capital’ — capital whose essential role is to buy cheap and sell dear but which itself does not create value.

"Merchant’s capital, therefore, participates in levelling surplus value to average profit, although it does not take part in its production. Thus the general rate of profit contains a deduction from surplus value due to merchant’s capital, hence a deduction from the profit of industrial capital."9

As for the retail workers,

"In one respect, such a commercial employee is a wage-worker like any other. In the first place, his labour-power is bought with the variable capital of the merchant, not with money expended as revenue, and consequently it is not bought for private service, but for the purpose of expanding the value of the capital advanced for it. In the second place, the value of his labour-power, and thus his wages, are determined as those of other wage-workers, i.e., by the cost of production and reproduction of his specific labour-power, not by the product of his labour. However, … Since the merchant, as mere agent of circulation, produces neither value nor surplus-value … it follows that the mercantile workers employed by him in these same functions cannot directly create surplus-value for him."10

And, just as the retail sector is in fact a drain on society’s real wealth so is the UK’s much-vaunted ‘financial services’ sector which now comprises almost 6 million workers. Even though the banks, head the DTI’s profitability list they are “nothing but a deduction from the surplus value since they operate with already realised values (even when realised in the form of creditors’ claims.)”11

In the next part of this article we will try to solve the real conundrum of how the financial sector — which represents a massive drain on surplus value in terms of the labour theory of value — should head the capitalists’ wealth creation list. Meanwhile, a last word on services.

Public Services Turned Into Commodities for Capital

As we have seen, there is no consistent capitalist definition of service work. For Marx service work by definition is unproductive because a service is not a commodity and the labour involved in producing a service creates use value but not exchange value. The bourgeoisie, on the other hand, include all sorts of labour — including commodity producing labour, but also unproductive labour which strictly belongs to the cost of circulating capital — in the category of services. If we look once again at the ONS workforce table, it is apparent that the largest single category — ‘health, education and public administration’, with 7.4m workers, comes closest to Marx’s definition of service work. Although in the main these workers do not receive a personal fee for the use value they provide, the wages of most of them are paid out of taxation, that is out of society’s revenue and though they provide a more or less useful service, the cost of their labour power is a drain on the overall pool of surplus value. Unlike with the much-vaunted financial sector, Gordon Brown and Co. are quick to perceive education, hospitals and welfare spending in general as a drain. Hence the cuts and also the attempts (without consciously realising it) to turn services into commodities by turning over care homes, aspects of medical care and certain branches of schooling, into the hands of private capital to run as a business. In this case services, previously paid for out of taxation, are turned into commodities where the ‘service provider’ has been turned into a value producing wage worker.

In practice it is difficult for capital to fully ‘commoditise’ genuine services but the growing involvement of private capital in the provision of public services — from central and local government outsourcing of supplies (worth £30bn to private capital last year) to the so-called private finance initiative (PFI) which currently includes more than 660 projects from Capita’s running of London’s traffic congestion charging scheme to the ill-fated involvement of Jarvis in railway maintenance and school building — gives companies access to revenue from taxation which they can then employ as capital to boost their profit rates or at any rate the value of the company’s shares. These efforts to turn revenue into capital and services into commodities are dwarfed by the financial returns accruing to the UK’s financial sector but they take place in the context of the international ‘freeing of the services market’ being negotiated in the Doha round of the WTO and are symptomatic of the desperation to find new sources of surplus value that typifies capital today.

ER

- 1In an aside on productive labour in the context of the total process of material production Marx clarifies that productive labour is not limited to those directly involved in the act of ‘working up raw material’:

"With the development of the specifically capitalist mode of production, in which many labourers work together in the production of the same commodity, the direct relation which their labour bears to the object produced naturally varies greatly. For example the unskilled labourers in a factory referred to earlier have nothing directly to do with the working up of the raw material. The workmen who function as overseers of those directly engaged in working up the raw material are one step further away; the works engineer has yet another relation and in the main works only with his brain, and so on. But the totality of these labourers, who possess labour-power of different value (although all the employed maintain much the same level) produce the result, which, considered as the result of the labour-process pure and simple, is expressed in a commodity or material product; and all together, as a workshop, they are the living production machine of these products—just as, taking the production process as a whole, they exchange their labour for capital and reproduce the capitalists’ money as capital, that is to say, as value producing surplus-value, as self-expanding value. It is indeed the characteristic feature of the capitalist mode of production that it separates the various kinds of labour from each other, therefore also mental and manual labour— or kinds of labour in which one or the other predominates—and distributes them among different people. This however does not prevent the material product from being the common product of these persons, or their common product embodied in material wealth; any more than on the other hand it prevents or in any way alters the relation of each one of these persons to capital being that of a wage-labourer and in this pre-eminent sense being that of a productive labourer. All these persons are not only directly engaged in the production of material wealth, but they exchange their labour directly for money as capital, and consequently directly reproduce, in addition to their wages, a surplus-value for the capitalist. Their labour consists of paid labour plus unpaid surplus-labour." [TSV part one, Lawrence and Wishart ed. pp.411-2]

- 2op.cit. p.413

- 3"But the relation between buyer and seller of this service has nothing to do with the relation of the productive labourer to capital, any more than has the relation between the buyer and seller of yarn." op.cit. p.412

- 4op.cit. p.165

- 5Financial Times 18.10.04

- 6TSV op.cit. p.411

- 7Quoted in the Financial Times, 13.5.05. For full quotation see the first part of this article in the previous issue.

- 8Depending on whether the media sector officially comes under ‘services’. The Office of National Statistics does not specify.

- 9Capital Vol. 3 p.286

- 10op.cit. pp.292-3

- 11Marx on money dealers’ profit, end of Ch.19 ‘Money Dealing Capital’, Vol. 3 of Capital, Lawrence and Wishart edition.

Comments

Pretty good read together

Pretty good read together with Part one.. Might query the phrase ''largely deducted from workers wages'' if this is meant to mean that workers including the same public sector workers actually pay these taxes (ie income tax) in the longer term, rather than the capitalists, and should therefore regard issues of taxation more generally as significant class issues?